Table of Contents

Introduction

Rishab Shetty’s Kantara was a cinematic triumph, a breathtaking journey into the mystical folklore of coastal Karnataka. The film introduced millions to the vibrant and divine tradition of Bhoota Kola and the legend of Panjurli, the boar demigod. We were captivated by the story of a king, a promise, and a deity who protects the forest and its people.

But like most cinematic adaptations of ancient legends, Kantara presented a version of the story that was palatable for a mass audience. The real folklore surrounding the Kola ritual and its demigods is far more primal, unsettling, and steeped in a darkness that would be too intense for mainstream cinema. The raw, untamed nature of these original legends reveals a world where divine justice is swift, brutal, and often bloody.

Beyond the Land Grant: The True Nature of the Bhootas

The film’s central conflict revolves around a land grant, a promise made by a king to the Panjurli Daiva in exchange for peace. While land disputes are a part of the lore, the primary role of many Bhootas (divine spirits) is far more visceral. They are not just guardians of the land; they are fierce protectors of the village community and upholders of a strict moral and social code. Disrespecting the Daiva or breaking a vow wasn’t just a legal issue—it was an invitation for divine wrath.

The Unseen Blood Sacrifices

One of the most significant aspects toned down for the film is the historical practice of blood sacrifice. In many traditional Kola rituals, the offering of blood was a crucial element to appease the more ferocious or “ugra” forms of the spirits. While today this is largely symbolic, often replaced with offerings of tender coconuts and other items, the ancient traditions involved the sacrifice of animals, most commonly chickens. This act symbolized a direct pact made in blood between the deity and the devotee, a primal exchange that underscores the life-and-death stakes of the ritual.

The Brutal Punishments of the Daiva

In Kantara, the landlord who betrays his ancestor’s promise meets a grim, supernaturally-ordained end. However, the traditional folklore is filled with tales of punishments that are far more graphic and terrifying. Legends speak of spirits inflicting gruesome diseases, causing madness, or wiping out entire family lineages for acts of disrespect.

One of the most feared demigods in the Tulu pantheon is Guliga. Often considered the fiery attendant of Panjurli, Guliga represents untamed, chaotic energy. His legends are filled with stories of him demanding blood, devouring spirits, and delivering a form of justice so savage it serves as a terrifying warning to all. The film’s antagonist faced a deity’s anger; in the original legends, he would have faced unimaginable torment.

The Possession: A Violent, Painful Transformation

The film beautifully portrays the Kola performer’s transformation as a divine and powerful moment. While it is certainly seen as divine, the oral traditions describe the process of possession as an intensely violent and physically agonizing experience. The performer, or “Daiva Patri,” doesn’t just act like the spirit; their body is believed to be a literal vessel, and the entry of a powerful, otherworldly force is not always gentle. The guttural cries, the contortions, and the feats of self-harm (like walking on hot coals) are not just for show—they are manifestations of a spirit whose raw power the human body can barely contain.

The Impure and the Forbidden

The folklore of Bhoota Kola is also governed by strict, ancient rules of purity and social order that are incredibly complex. A single misstep in the ritual process, a transgression by an “impure” person, or the breaking of a taboo could nullify the entire ceremony and invite the wrath of the Bhoota. These rules reflect a rigid social structure and a worldview where the lines between the sacred and profane are absolute and crossing them has dire consequences.

The Realism of Fear

The reverence shown to the Daiva in the film is accurate, but it only scratches the surface of the emotion that governs these traditions: a profound and primal fear. This isn’t the fear of a monster, but a deep, trembling respect for a powerful, unpredictable divine force that can grant prosperity just as easily as it can deliver ruin. It is this raw, untamed nature of the divine that gives the Kola its true power.

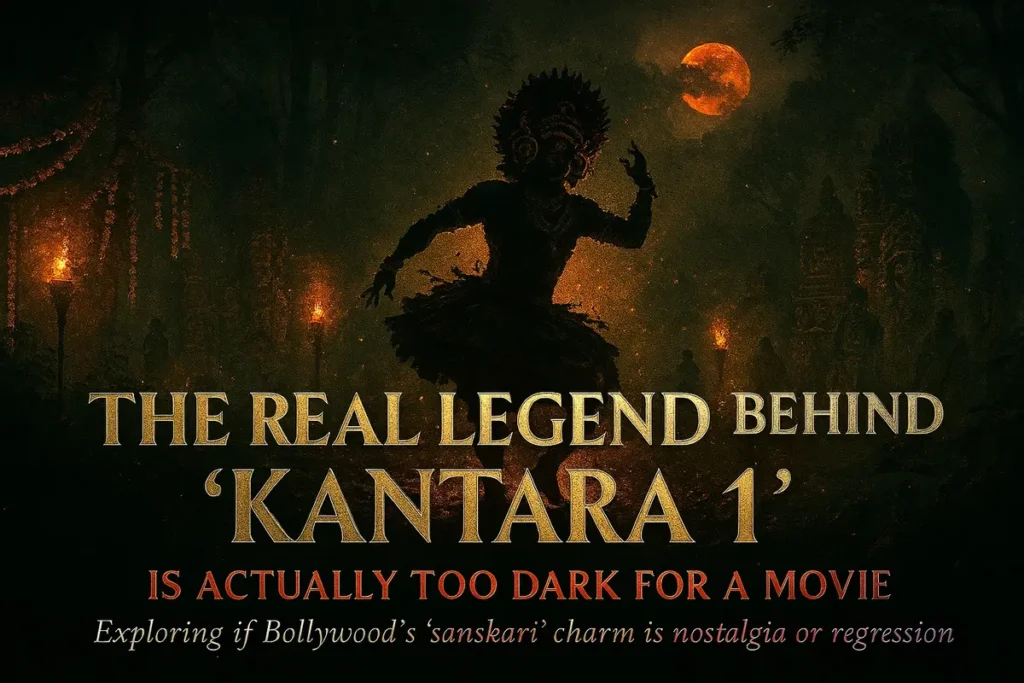

A Story Too Primal for the Screen

Kantara did a masterful job of translating a piece of this ancient world for modern eyes. But the true legends of the Bhootas are not neat parables. They are raw, chaotic, and filled with the blood, fear, and fire of a time when the boundary between the human and spirit worlds was terrifyingly thin. It’s a folklore that reminds us that the divine can be as ferocious as it is protective, a truth perhaps too dark for the silver screen.